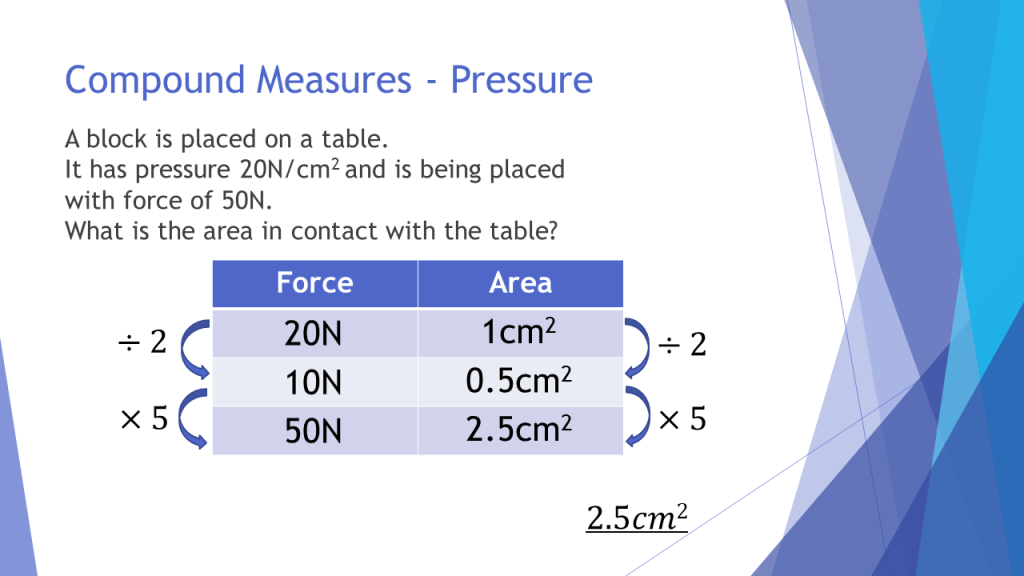

Yesterday, at MathsConf28 in Gloucester, I shared my obsession with Ratio Tables as a tool for multiplicative thinking. It followed on from my session back at MathsConf24 where I talked about using ratio tables for teaching compound measures. You can read about that session here.

If you are just here for the slides from the session, (with my mathematical error fixed!!!) here they are:

But I have included a bonus topic to use ratio tables with right at the end, so maybe scroll down too!

A Summary of the Session

I am incredibly passionate about students developing their multiplicative reasoning, as it underpins so much of the national curriculum… heck, mathematics as a whole! So once I found a structure that worked to expose this, I ran with it.

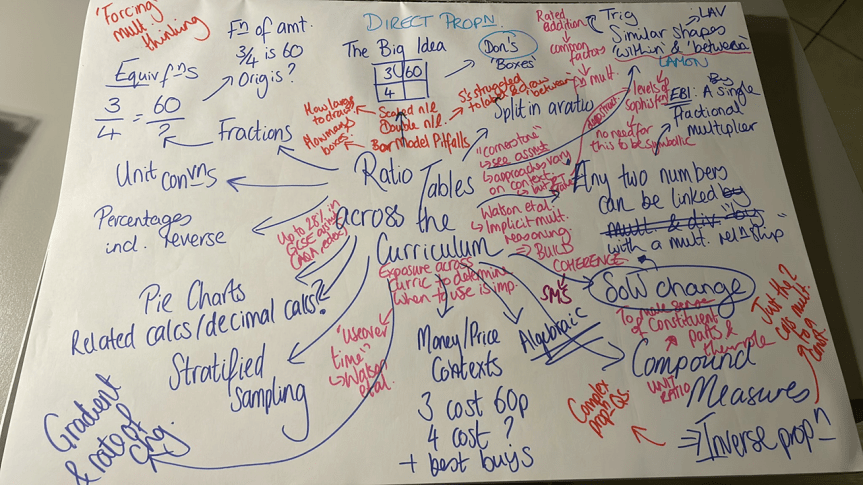

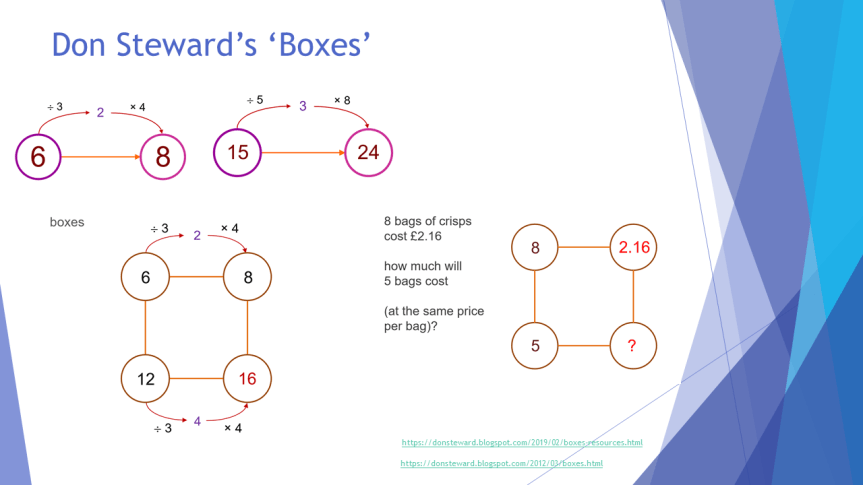

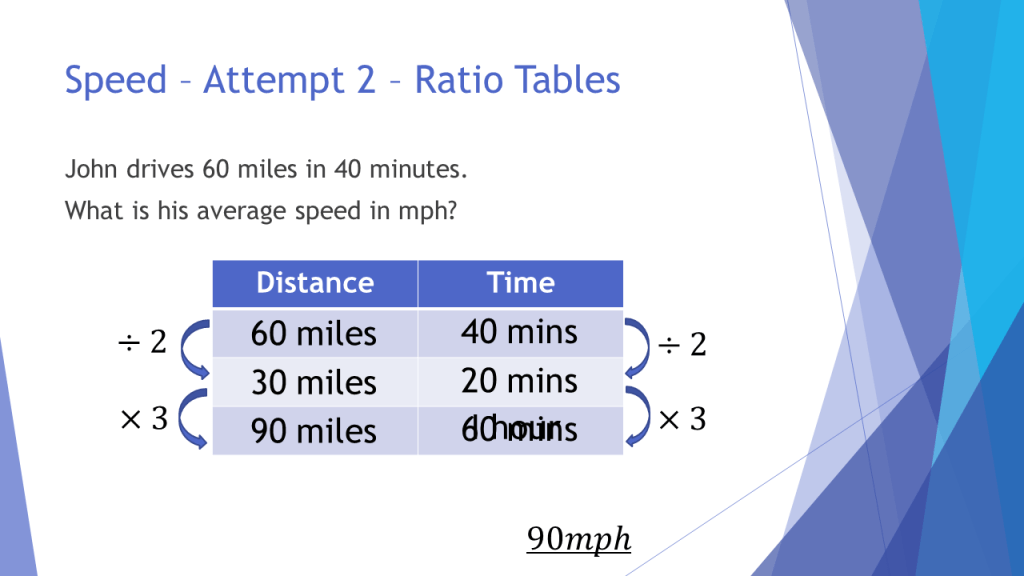

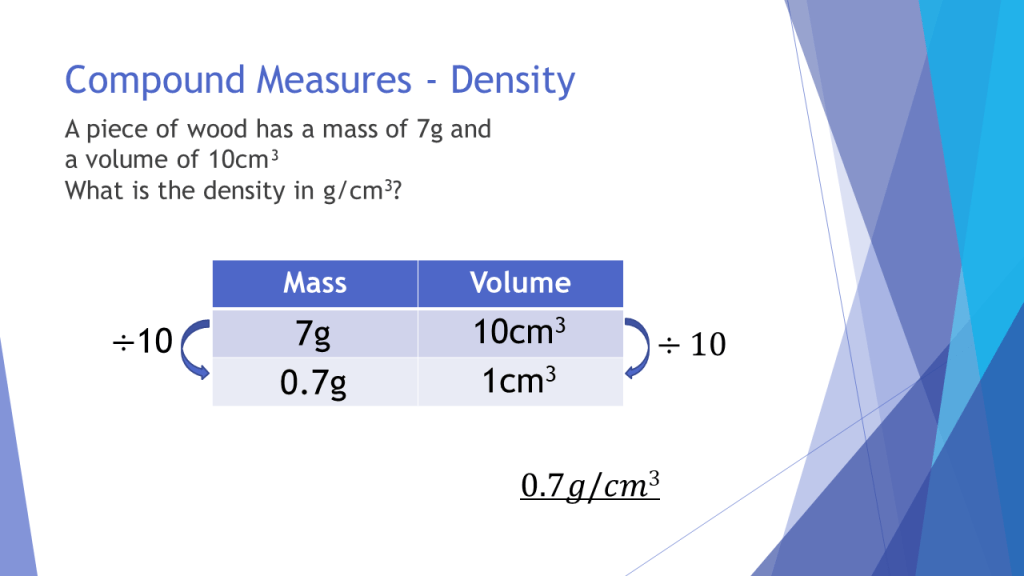

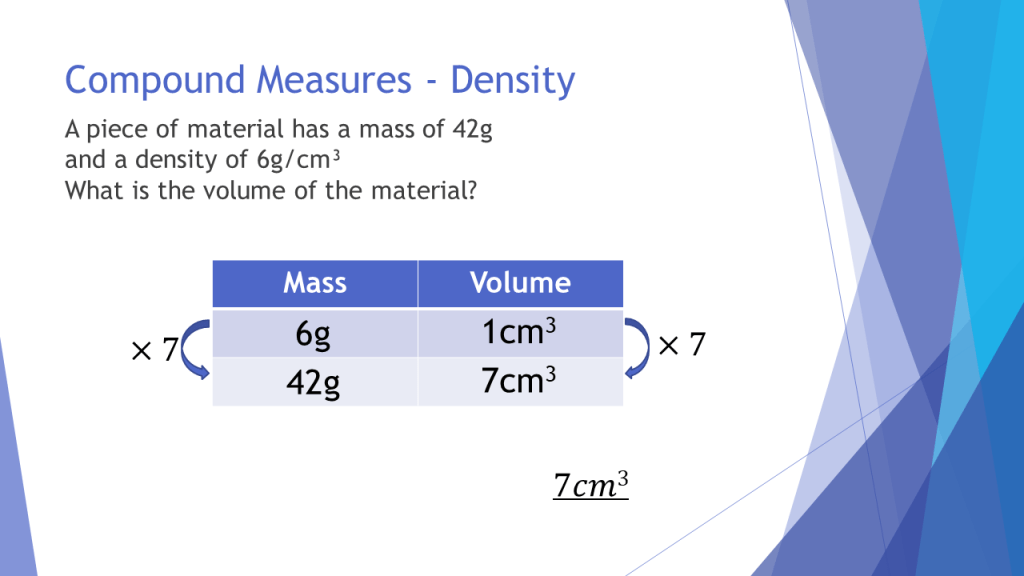

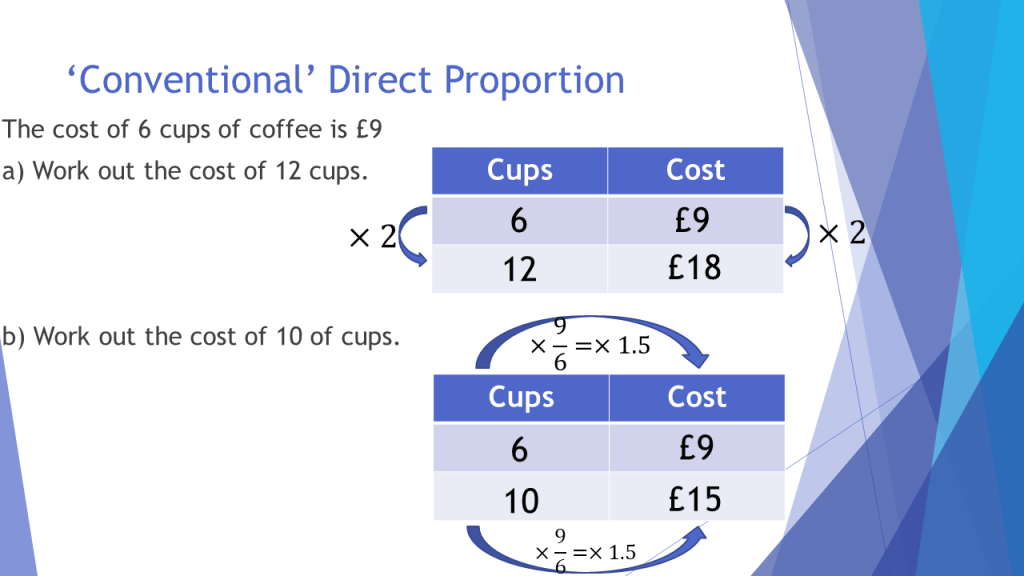

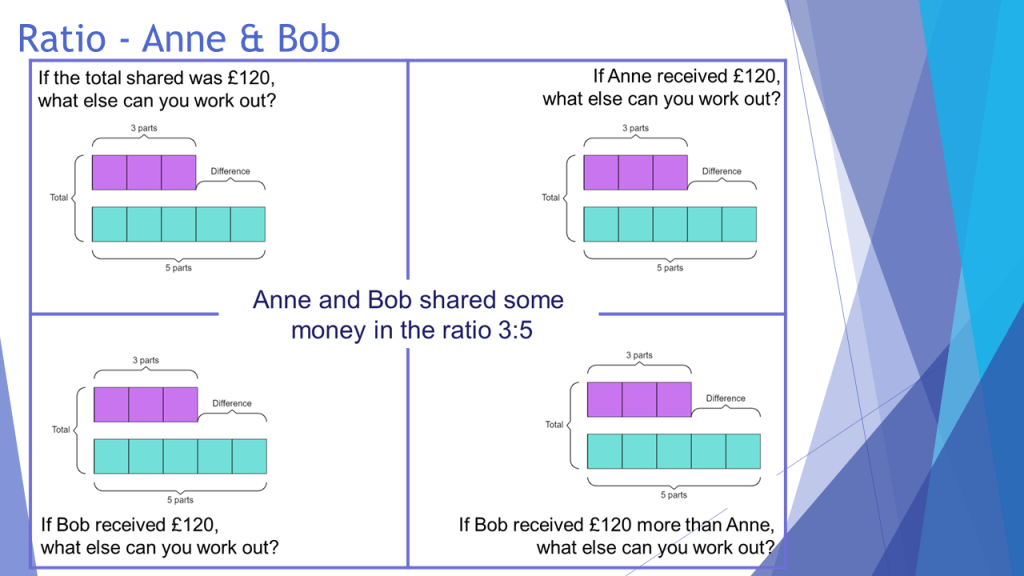

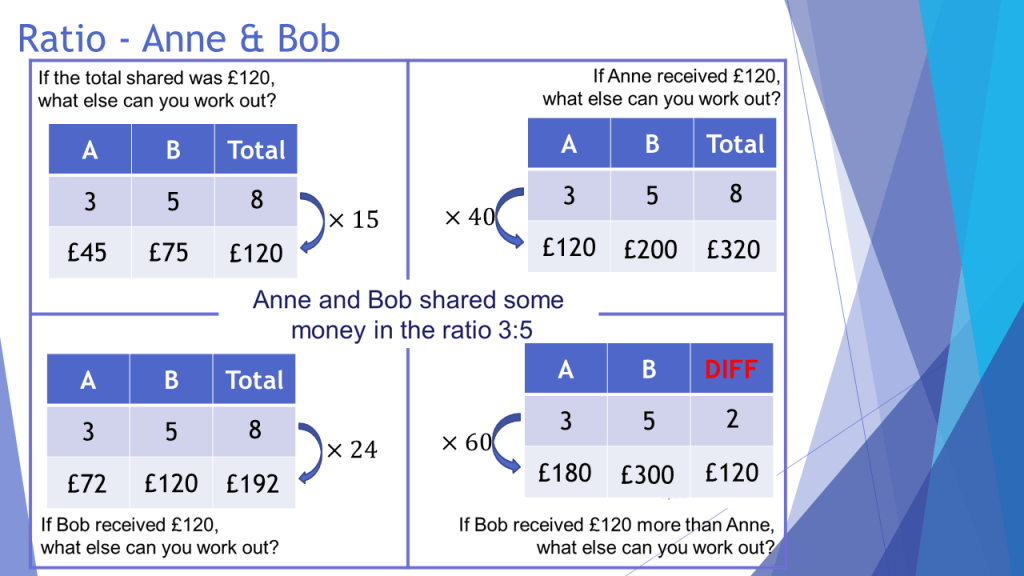

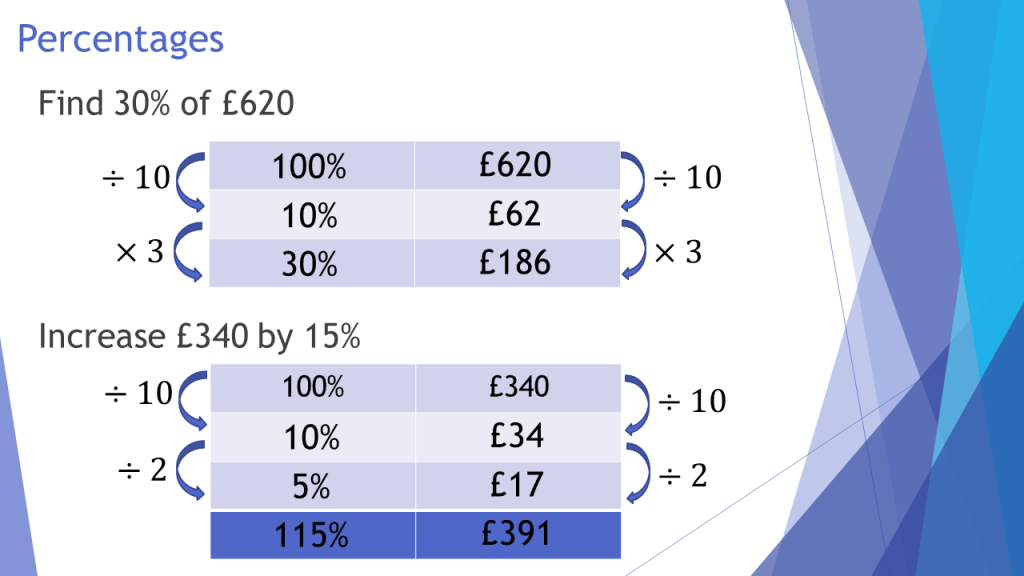

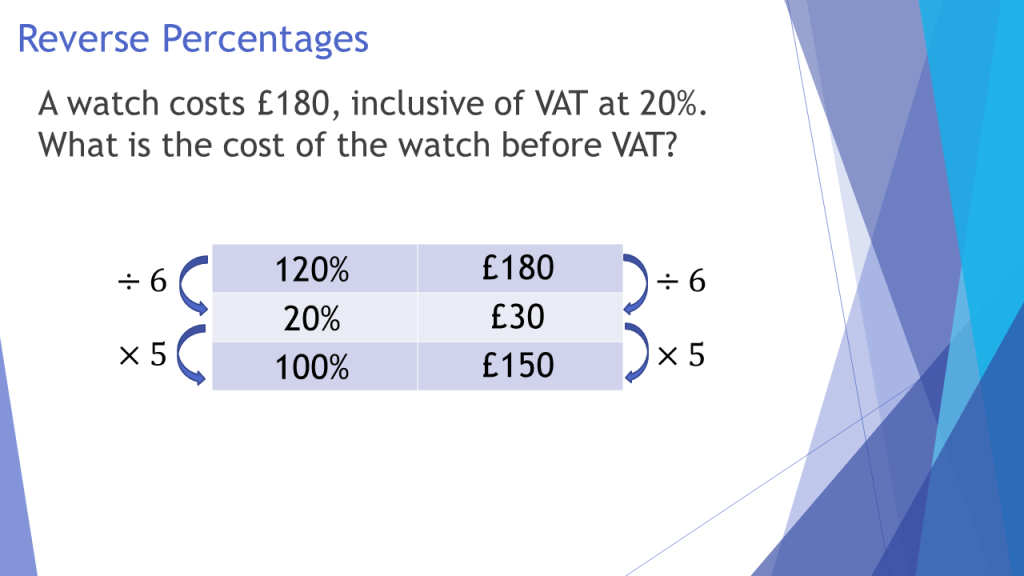

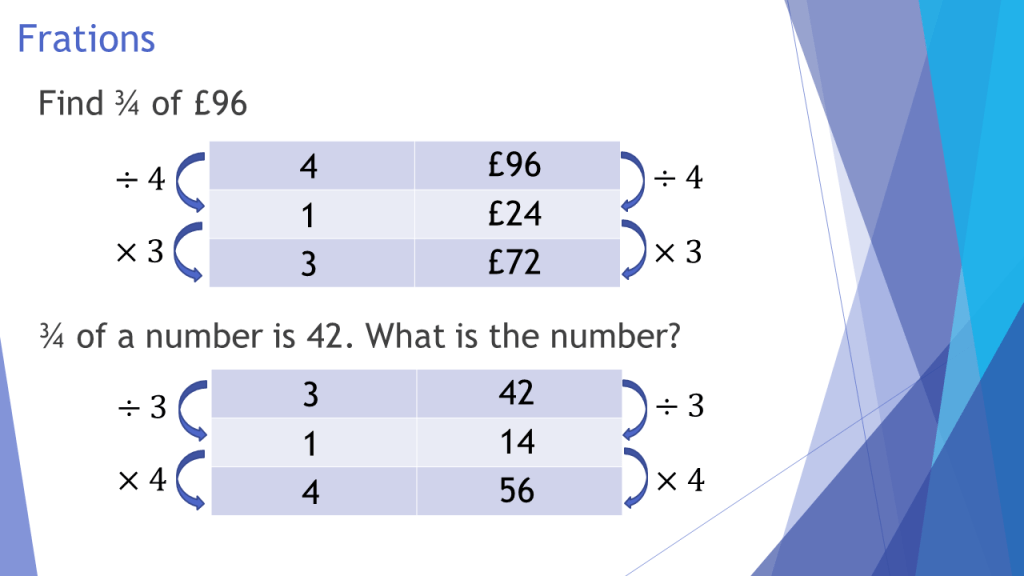

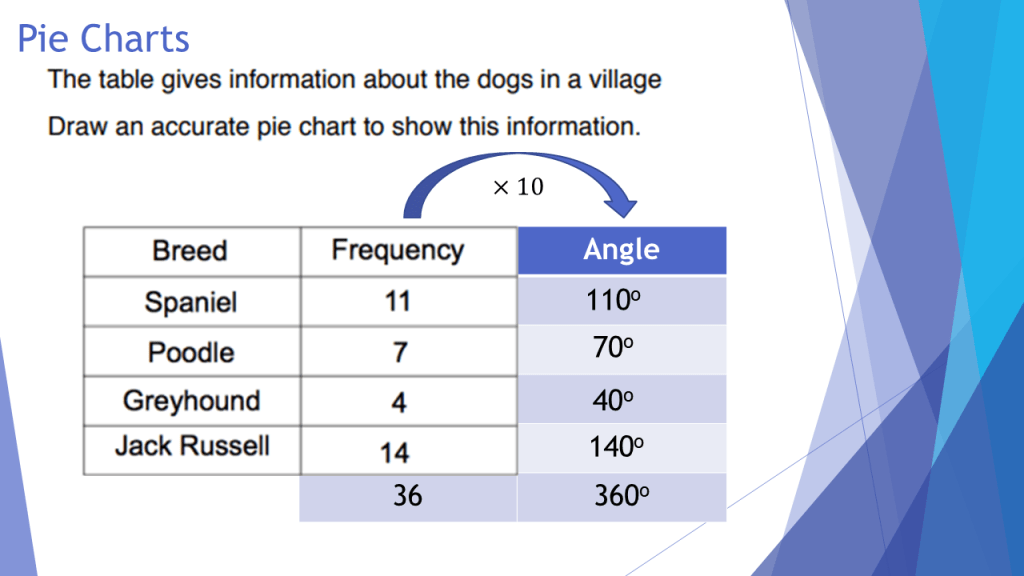

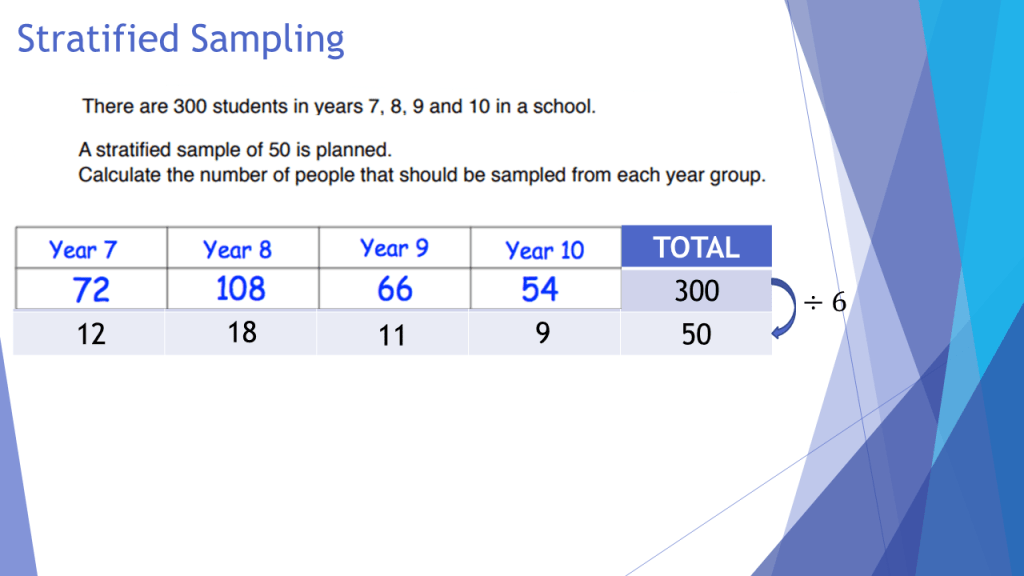

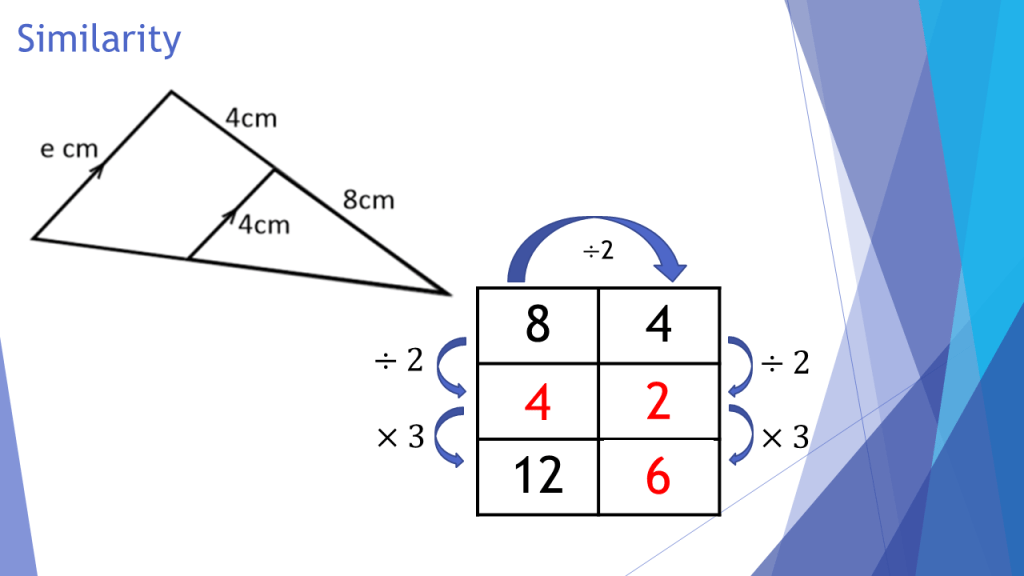

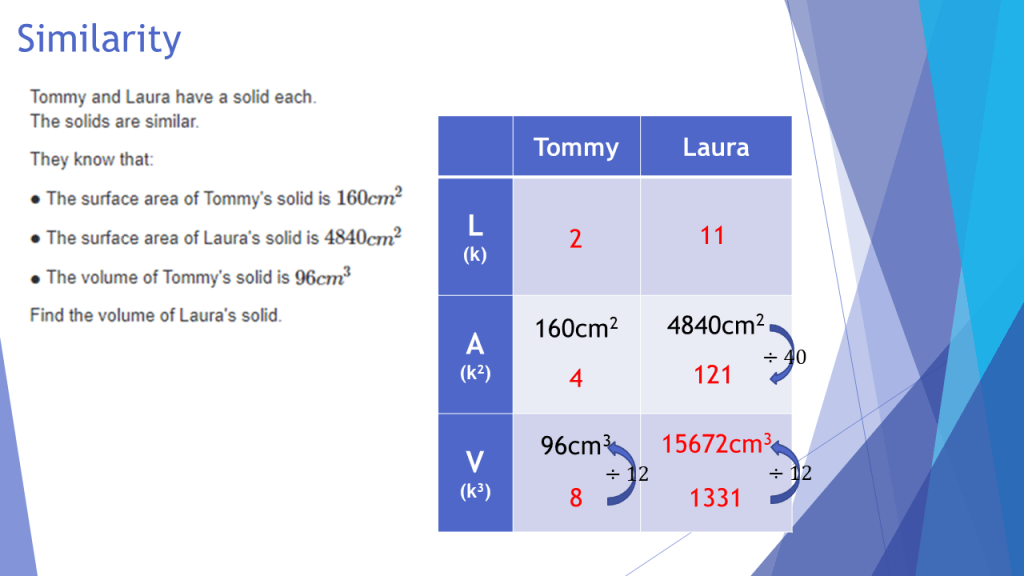

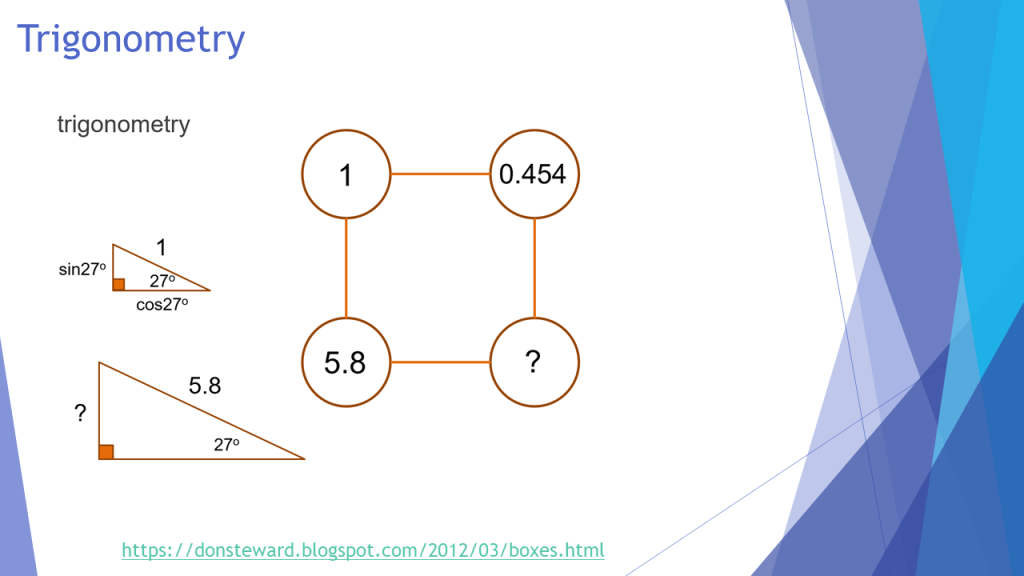

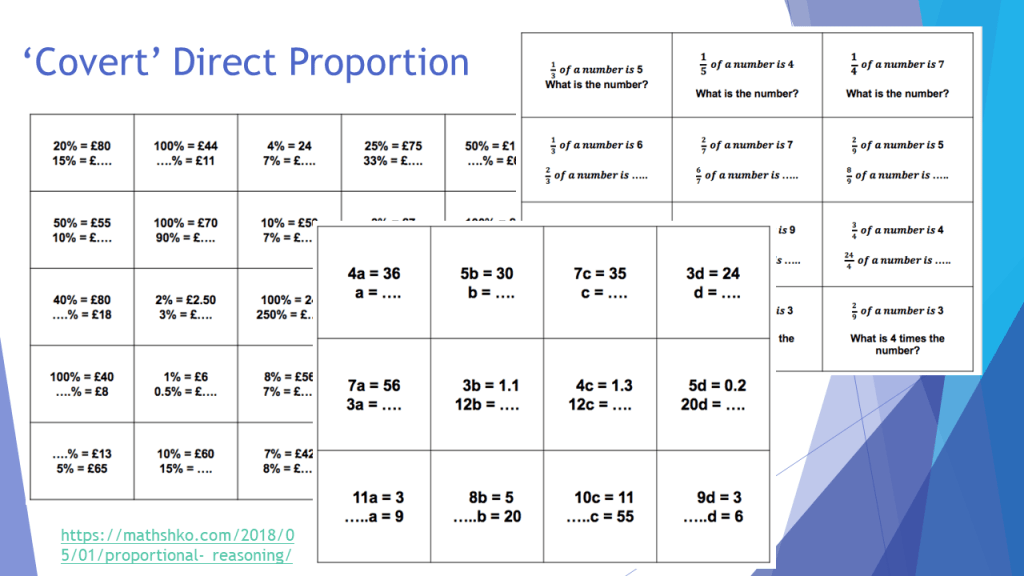

The more I used ratio tables to help with my teaching of compound measures, the more aware I became of their usefulness across the curriculum. I started noticing that I already used the same kind of thinking with questions involving percentages (writing 100% is ____, then 10% is____ on the line below etc.), pie charts (by adding an extra column for the angles), and recipe problems (a new column for a different number of servings). Gradually, I built up a list of other places that I could see it being utilised, aided by Don Steward’s wonderful ‘Boxes‘ resource. I have slowly built up my repertoire to use them as much as possible in my own teaching… It became a bit of an obsession.

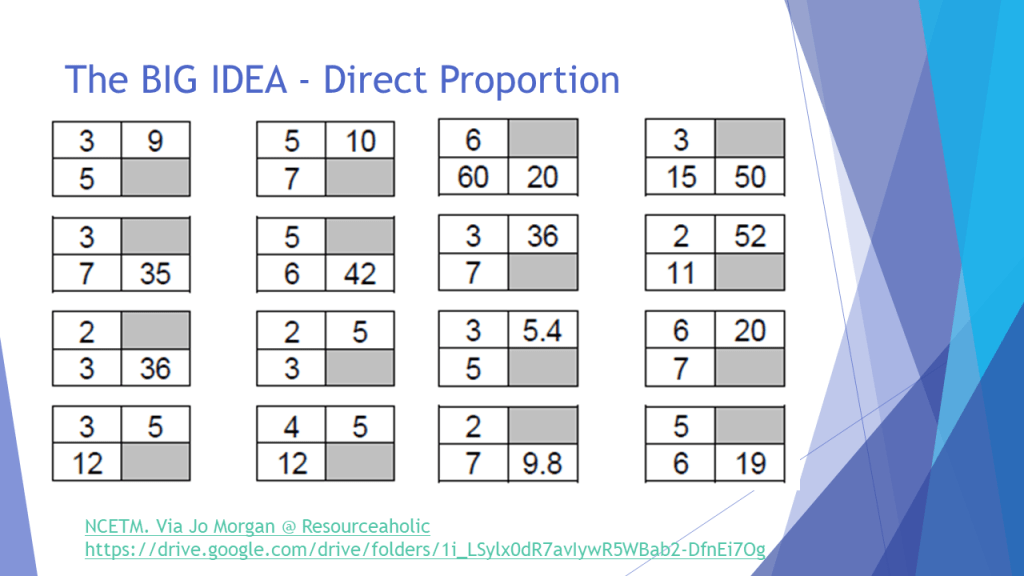

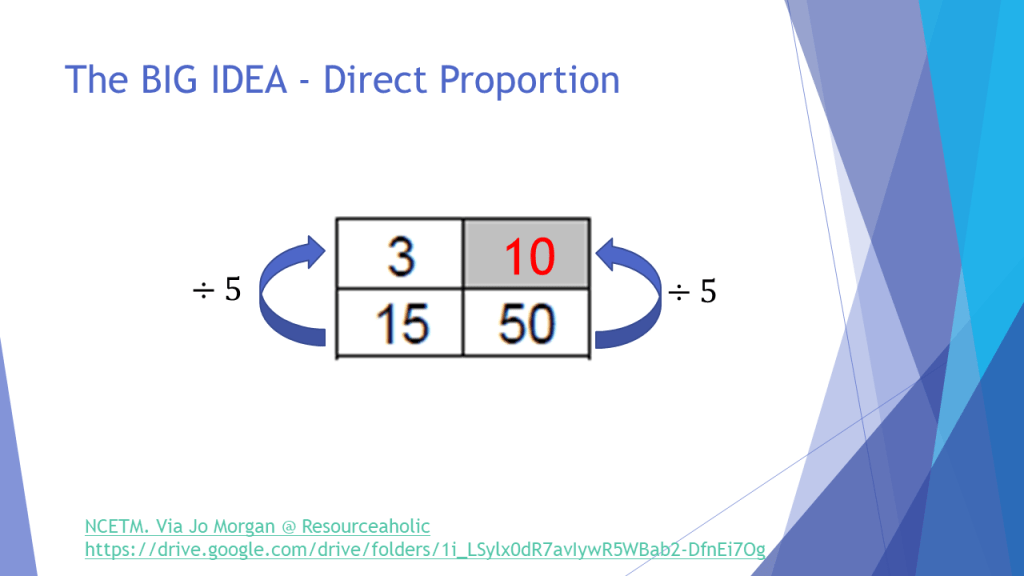

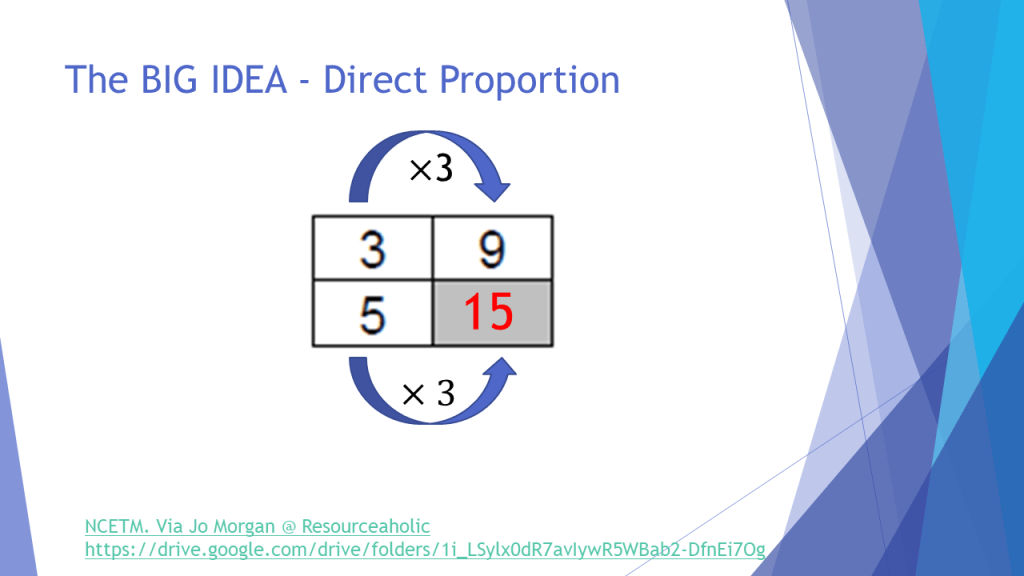

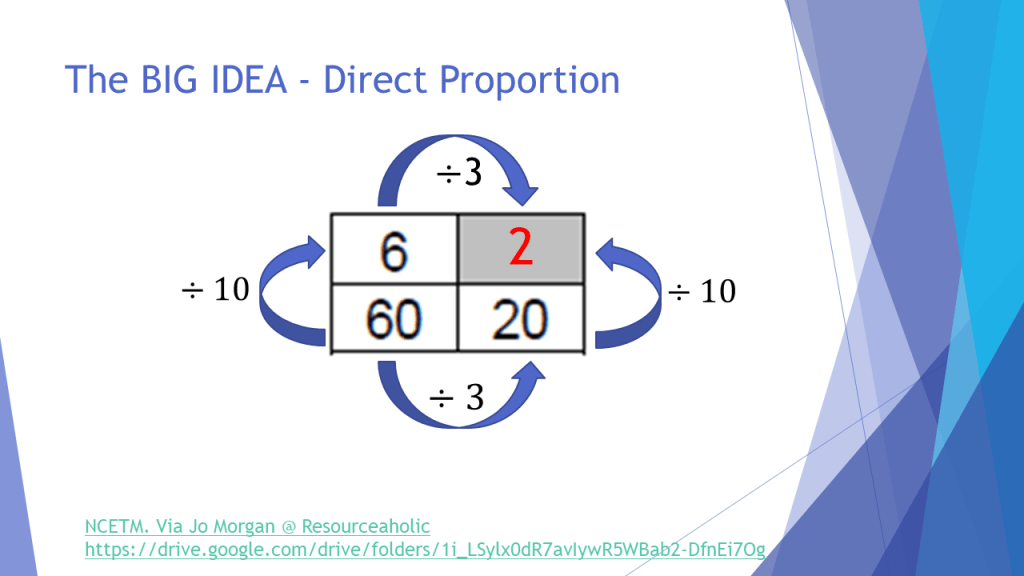

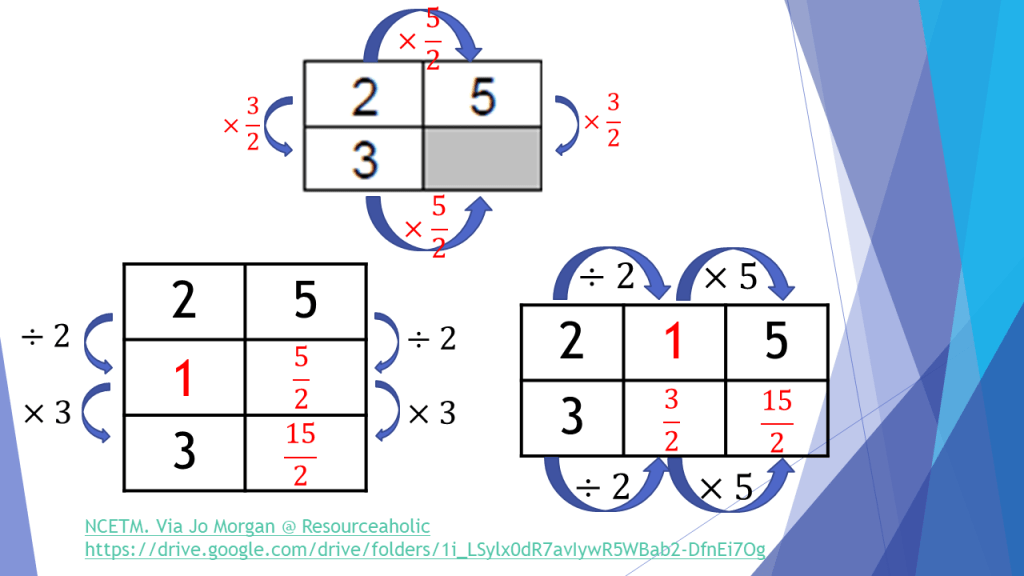

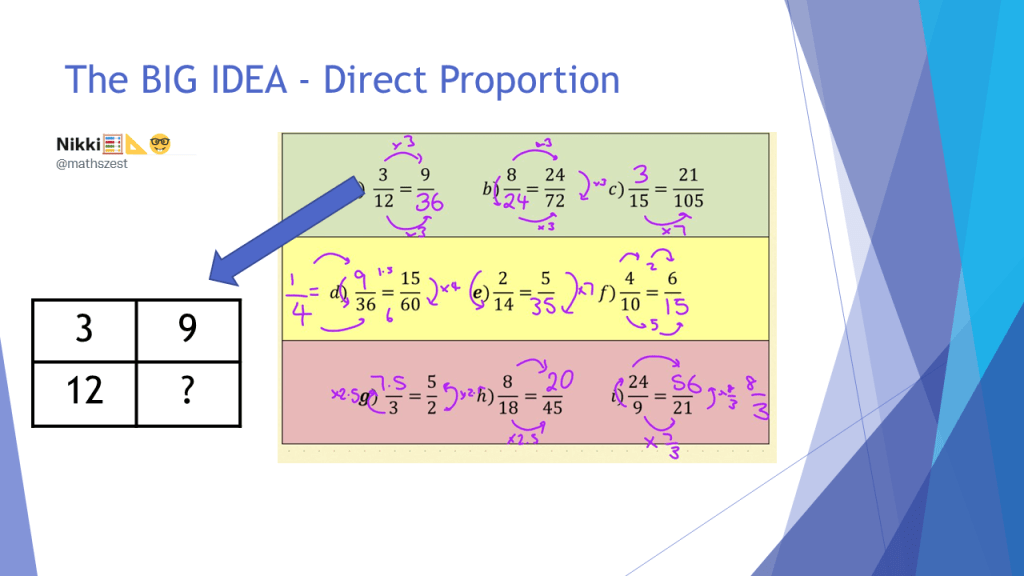

One of the first things I realised was that students needed help to think multiplicatively, rather than additively. When I researched this for my PG Cert, I was grateful to read that many other people had found the same issue too. So I set about getting students to use the tables without headings in the initial stages… thinking about how to get between different numbers with multiplication and division ONLY. This felt like a bit of a game to start off with, mirroring the ‘Boxes’ resource, and sometimes even using ‘Broken Calulator’ tasks to force the issue slightly. You can find out more about this part of my thinking on my ‘Multiplicative Reasoning’ Planning to Teach Secondary Maths video that I made for the NCETM last year… so I will leave the details of this out of the blog today. It did, however, lead me to this lovely resource, linked by Jo Morgan on Resourceaholic, originally from the NCETM.

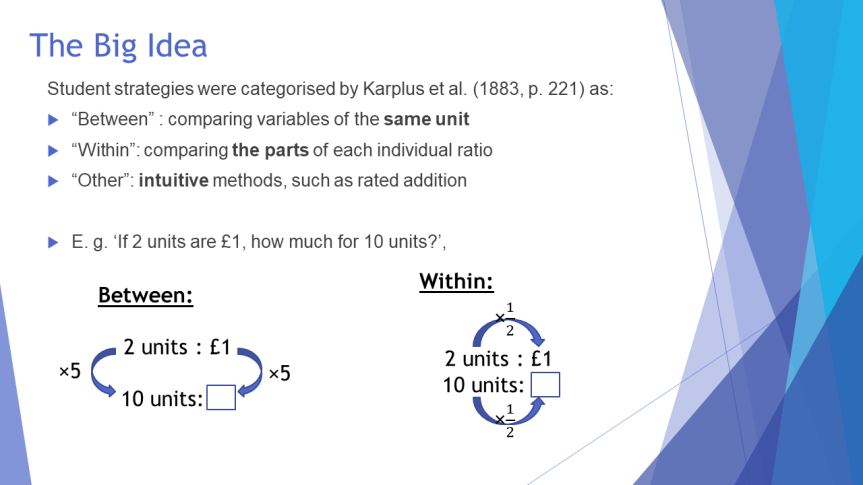

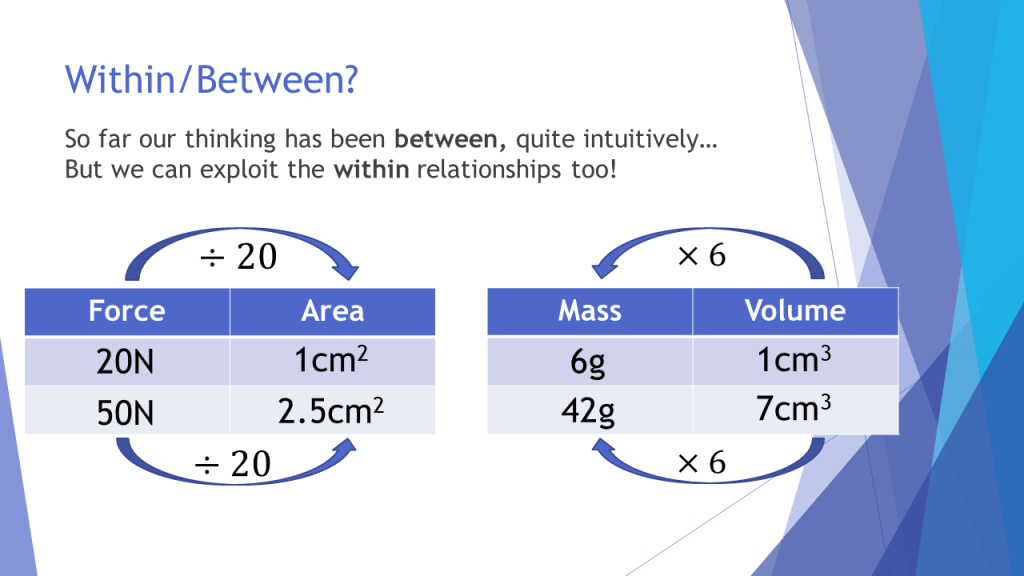

In my session, I explained how this helped my students consider both “within” and “between” strategies for proportional reasoning a little more.

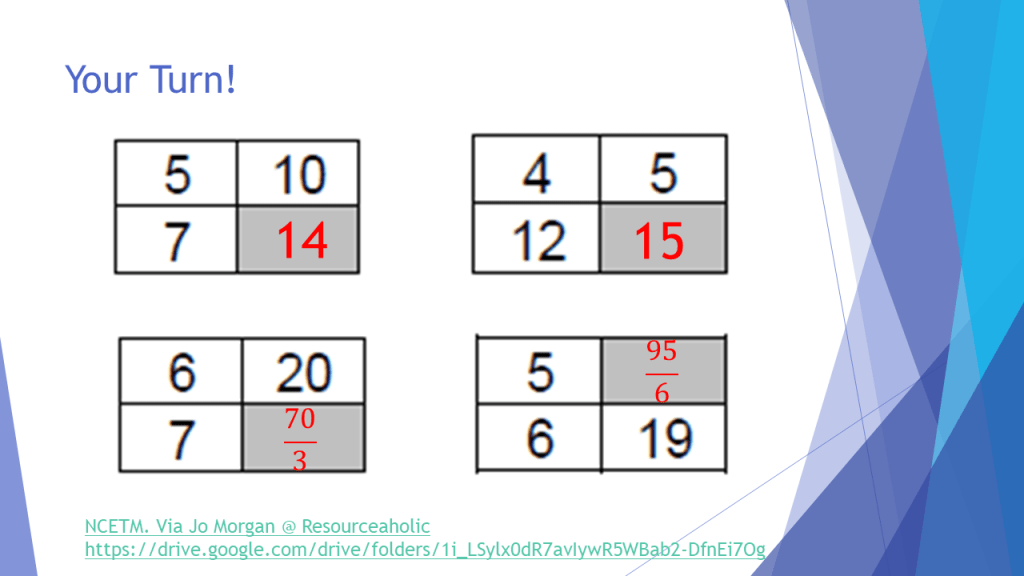

You can get infinite numbers of these with various different difficulty levels, with negatives and decimals etc. from the fabulous MathsBot here.

When teaching proportionality, it is often more intuitive for us to think about linking two elements of the same unit, and this means we have a pre-disposition to working in one direction within ratios/ratio tables, depending on where we place the headings. Removing these meant that students were invited to look both “across and down” the boxes. Eventually, some could even link the two through one single fractional multiplier, rather than adding on rows/columns as shown above.

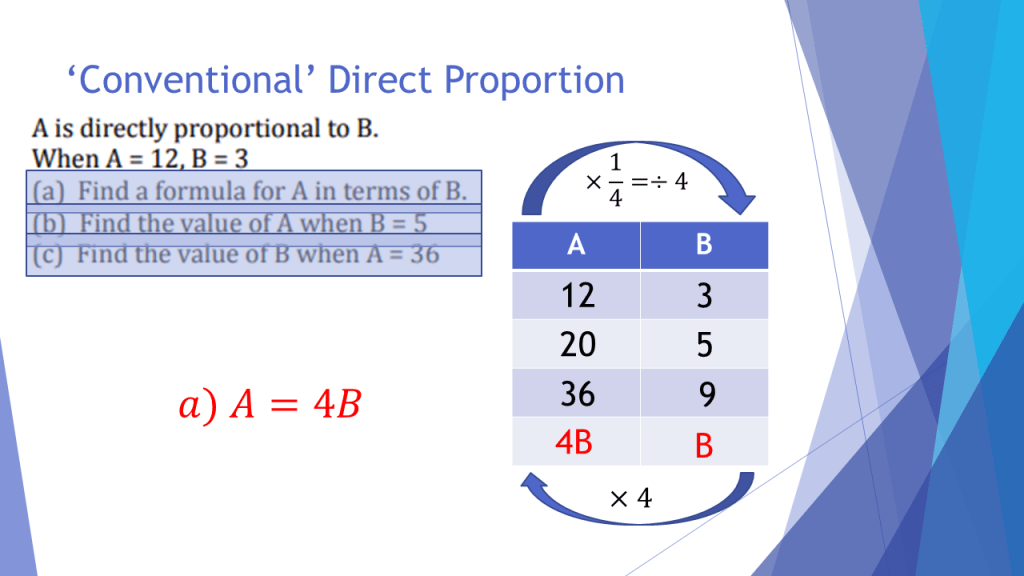

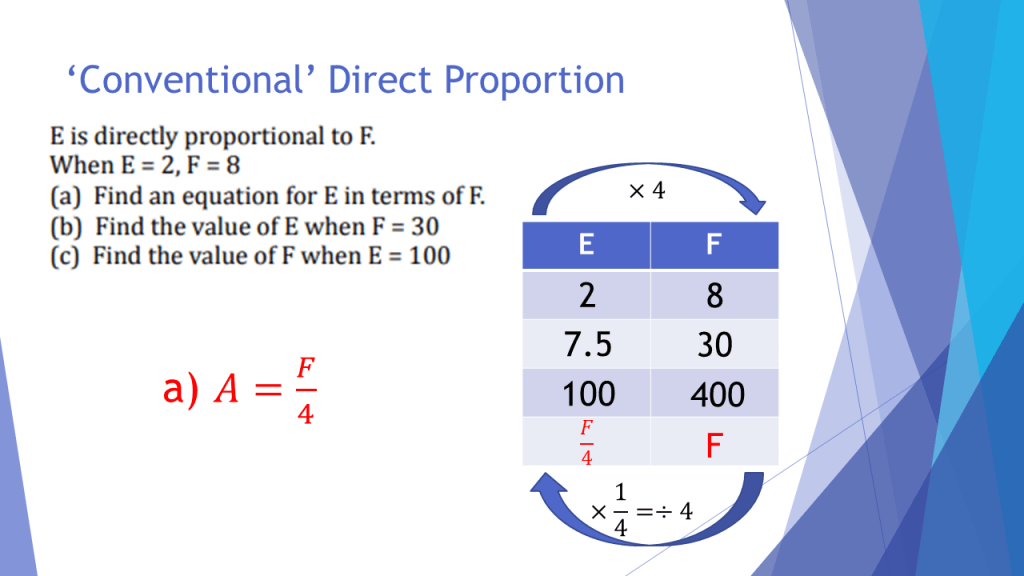

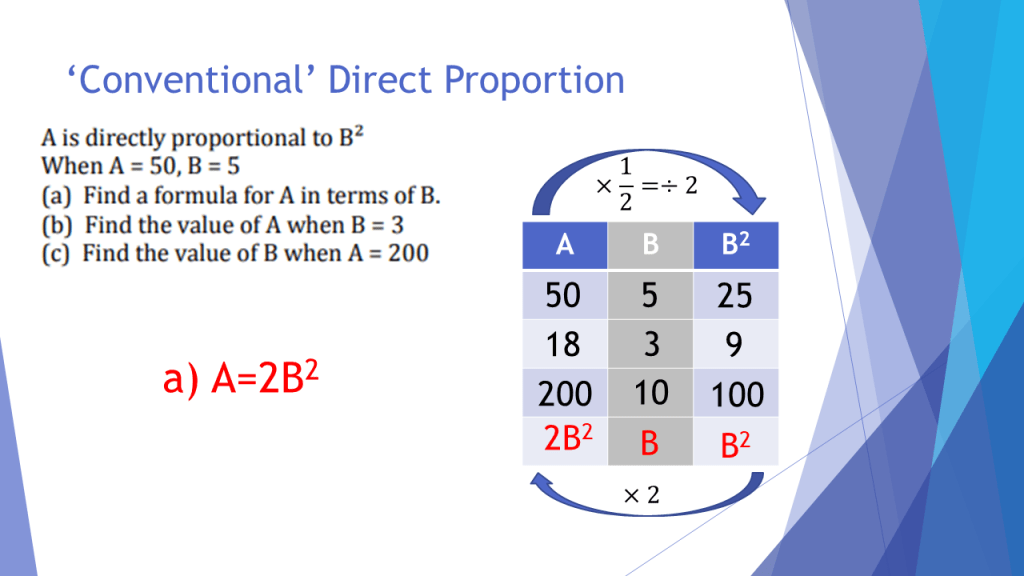

This then helped them to do the same when the headings retuned in the various contexts I shared in the second part of the session, which you can see below. The big thing here is that the maths is no different in each of these contests, just the numbers. Once students have the representation of the ratio table, and the ability to work “within” and “between”, they have accessed the structure of multiple mathematical ideas at once.

Gradient & Ratio Tables

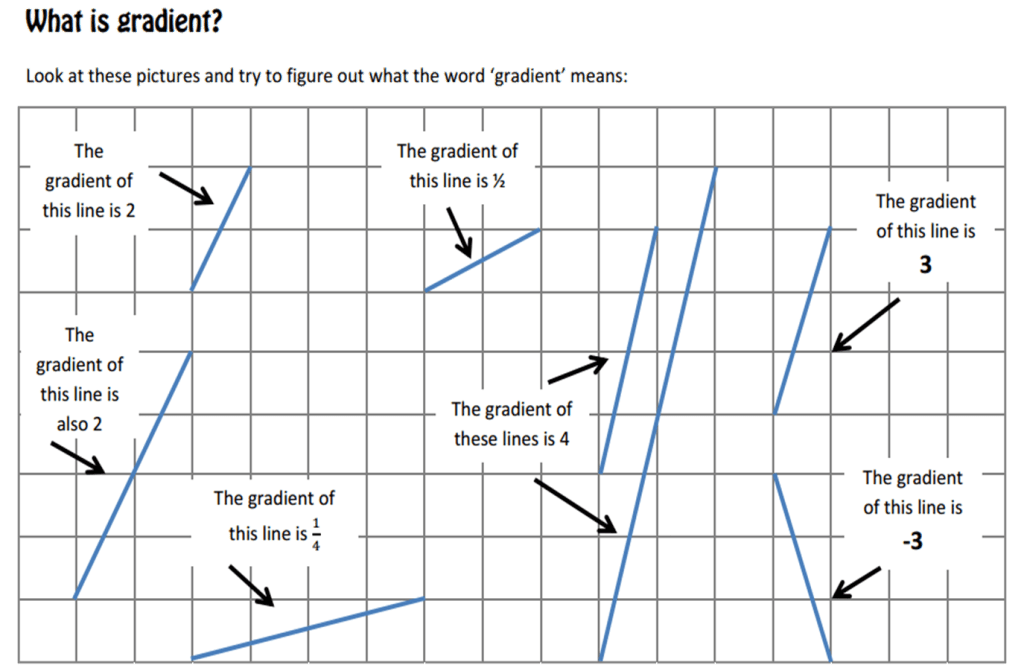

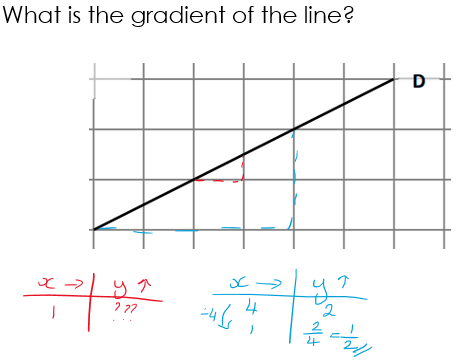

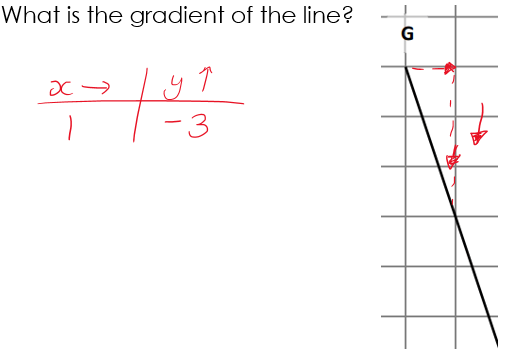

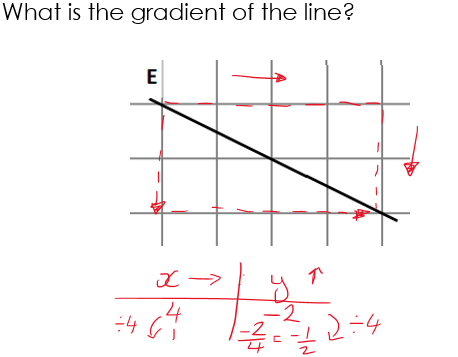

One application I didn’t include, which I regret to the highest degree today, is the use of the ratio table to help with gradient and rate of change questions as a while. Before beginning calculations, I gave them the resource below from MathsPad. There was a lot of discussion about slopes of lines and how we could measure them or how we might come up with a standard way to describe this.

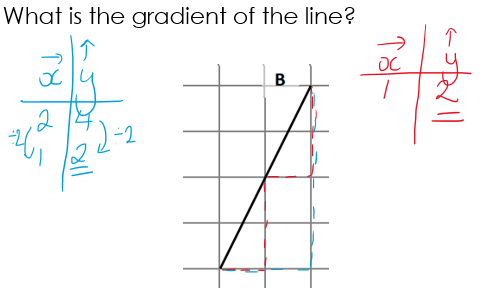

They decided we needed a standard reference point so we were always comparing any two lines “fairly”, with some noting that the shorter line with gradient of 4 was ‘inside’ the longer one. This is where the definition of gradient as “the change in the y direction for one unit in the x direction” became vital. So, again, we were considering a unit ratio, like we do with compound measures, but this time with “change in x” as the unit. There are some examples below. Making the direction clear, likening this to x and y axes and vector notation from the start, it meant that students were able to extend this to negative gradients quickly, and their familiarity with ratio tables and fractions meant that fractional gradients were also less of a problem than usual!

Summary

There are so many places where multiplicative reasoning is used in maths – both explicitly and implicity. For me, my students having a ratio table as a representaiton of this has allowed them to access and have SUCCESS with so many areas of the subject that they struggled with before. For me that is a victory, and that’s why I wanted to share it with you all. But it has not been a quick-fix.

It is important that you see this as an incremental change, that took a year in my own practice to develop, and then another year to embed in my department, including changes in the scheme of work and lots of CPD sessions. Though there are elements of this you can take away and pick up in lessons next week (I hope!), the fundamental idea here is to improve multiplcative thinking for our students, and so I implore you to consider how to do this with ratio tables, bar models, double number lines, algebra… and I refer you to Anne Watson:

What I would also like to say, to end the post, is a massive thank you to everyone that came to the session yesterday, everyone that wished me luck on my way to it, or smiled at me while I was speaking, or maybe you were brave enough to answer my questions about your strategies, or said something kind about the session on Twitter. MathsConf and the maths twitter community has given me so much over the past 6 years, and I often struggle to see my own contribution to that – but yesterday I really felt like I had given something back. I have gained so many wonderful ideas for my teaching and made some of the most brilliant friends I could ask for through this community, but the biggest thing I got from yesterday was a belief in myself. Thank you for allowing me to share my experiences and have them so warmly received. You are all wonderful.

I could talk about this forever, so please feel free to comment, tweet or email me, and I will gladly share any other resources I have to explain my ideas further.

References:

Much of the session came from reserch I did for my PGCert over the summer and as such, I need to credit the work below which was instrumental to my development of my own ideas:

- Brown, M., Küchemann, D., & Hodgen, J. (2010). The struggle to achieve multiplicative reasoning 11-14. In M. Joubert, & P. Andrews (Ed.), Proceedings of the British Congress for Mathematics Education. 30, pp. 49-56. University of Manchester: BCME. Retrieved Aug 13, 2021, from http://iccams-maths.org/publications/

- Foster, C. (2021). On hating formula triangles. Mathematics in School, 30-32.

- Karplus, R., Pulos, S., & Stage, E. K. (1983). Early Adolescents’ Proportional Reasoning on ‘Rate’ Problems. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 14(3), 219-233. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00410539

- Lamon, S. J. (1993). Ratio and Proportion: Connecting Content and Children’s Thinking. Journal For Research in Mathematics Education, 24(1), 41-61. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/749385

- Lamon, S. J. (1994). Ratio and Proportion: Cognitive Foundations in Unitizing and Norming. (G. Harel, & J. Confrey, Eds.) 90-121. Retrieved Aug 11, 2021, from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/

- Stein, M., Engle, R., Smith, M., & Hughes, E. (2008). Orchestrating Productive Mathematical Discussions: Five Practices for Helping Teachers Move Beyond Show and Tell. Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 10(4), 313-340. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10986060802229675

- Watson, A., Jones, K., & Pratt, D. (2013). Key Ideas in Teaching Mathematics; Research-based guidance for ages 9-19. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Superb: thank you Kathryn!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Kathryn. I am an online tutor and came across this blog a while back. I have been using some of these ideas successfully, thank you!. I am about to start an online course for Functional Skills L2 for home educated learners. It will be 2 hours a week live over 35 weeks. My intention is to spend the first part of the course teaching exactly this sort of proportional reasoning. Do I have long enough? I am also thinking of using the area model of multiplication for multiplying and dividing fractions and decimals and percentage increase/decrease, there is a lot of cross over with the ‘boxes’ representation. I think the area model for is also a really strong representation for percentage increase and decrease for example. Too much to introduce both models? Not enough time? I would be interested in your thoughts.

LikeLike

Hi Darren, I don’t know much about the functional maths course. But these both sound excellent representations to share, really showing understanding and bringing it to your students. I hope it goes well!

LikeLike